Quick Intro

LeetArxiv is a successor to Papers With Code after the latter shutdown.

Here’s the Polymarket bet on touching Satoshi's wallet..

Here is 12 months of Perplexity Pro on us.

Here’s 20 dollars to send money abroad.

Here are some free gpu credits :)

Quick Summary

This paper introduces a fast sub-exponential algorithm for solving discrete logarithms over the set of complex numbers of type -2: the ring of Gaussian integers.

As usual, here’s the Python Google Colab link and here’s the GitHub with both C and Python.

*Jump to Section 3.0 for the bitcoin content.

1.0 Paper Introduction

The 1991 paper Computation of Discrete Logarithms in Prime Fields (LaMacchia & Odlyzko, 1991)1 demonstrates the ‘Gaussian Integers’ approach to collecting relations for an index calculus-style attack on discrete logarithms.

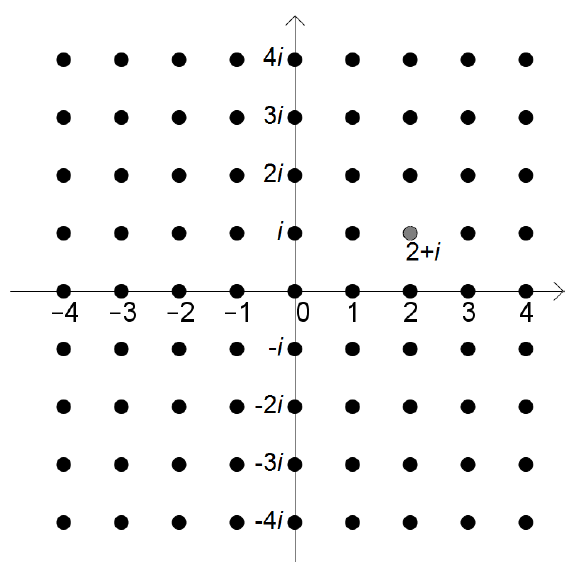

Gaussian integers are imaginary numbers from high school math.

We assume familiarity with index calculus techniques. This is part of our series on Practical Index Calculus for Computer Programmers.

Part 1: Discrete Logarithms and the Index Calculus Solution.

Part 2: Solving Pell Equations with Index Calculus and Algebraic Numbers.

Part 3: Solving Index Calculus Equations over Integers and Finite Fields.

Part 4.1 : Pollard Kangaroo when Index Calculus Fails.

Part 4.2 : Pohlig-Hellman Attack.

Part 5 : Smart Attack on Anomalous Curves.

Part 6: Hacking Dormant Bitcoin Wallets in C.

2.0 Sieving Algorithms

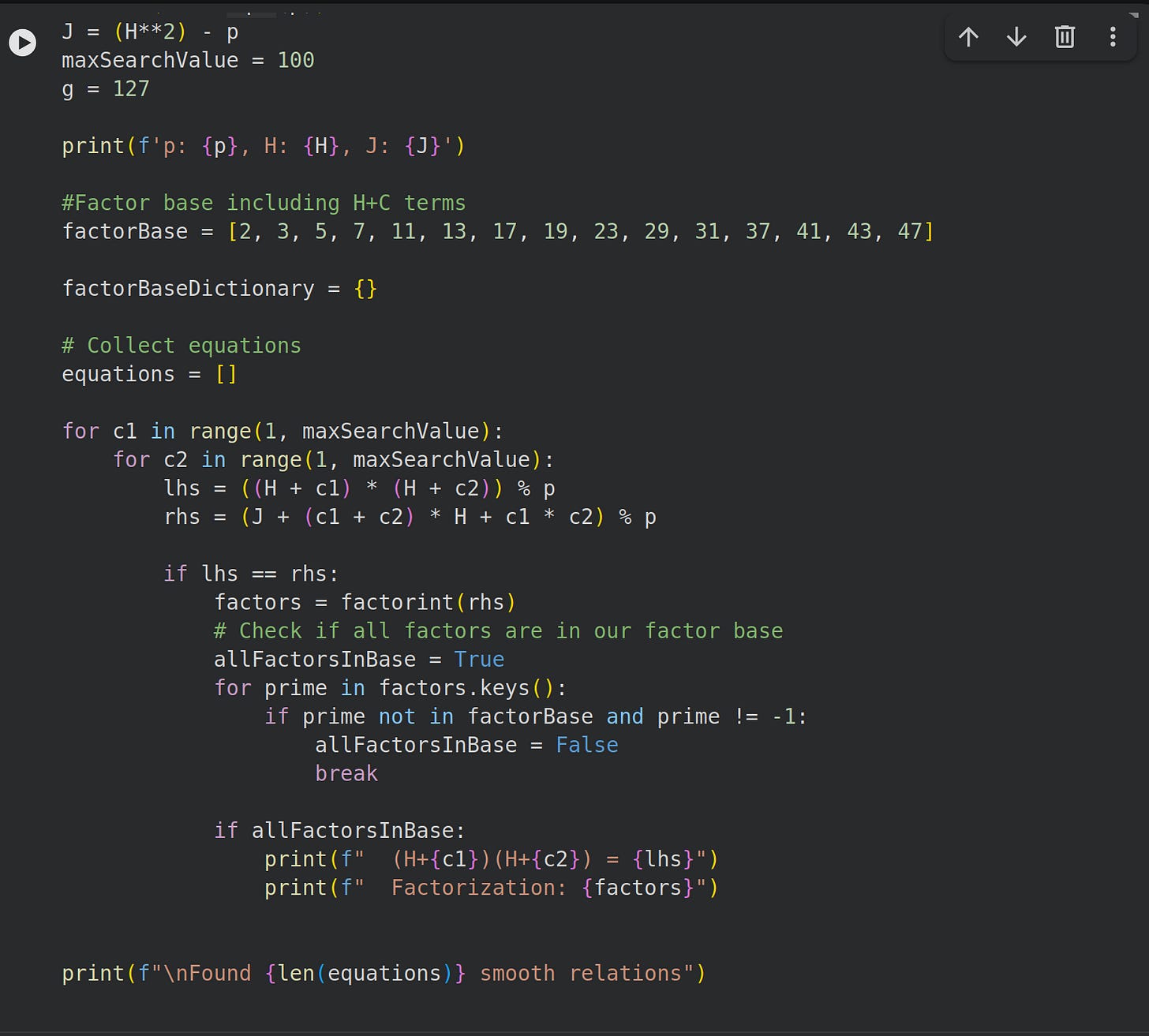

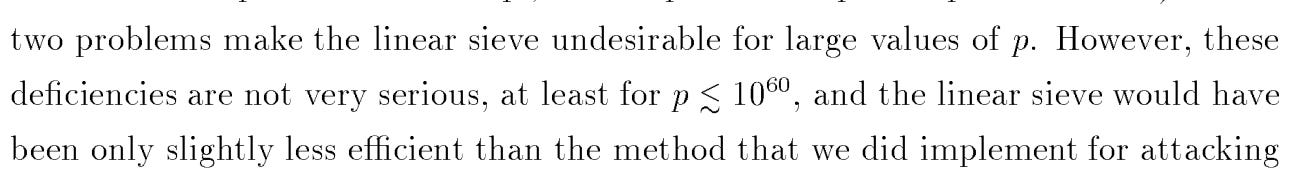

The authors introduce two sieving algorithms, the linear sieve and the gaussian integer sieve.

They demonstrate the linear sieve’s limitations and introduce the gaussian sieve in its place.

2.1 Linear Sieve

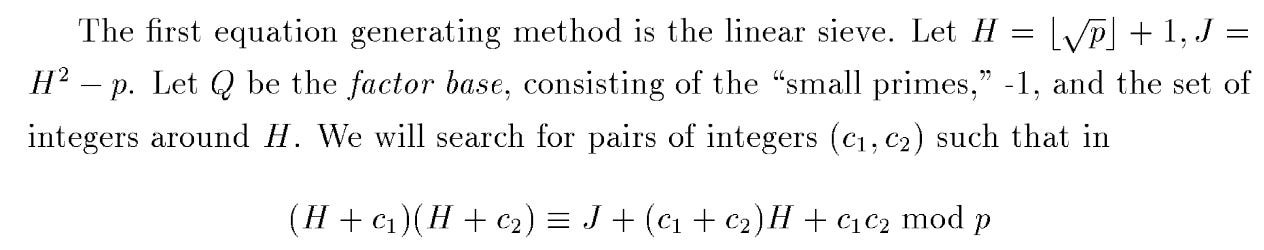

The authors propose searching for relations of the form above.

We demonstrate relation collection in this Google Colab notebook.

Two challenges are apparent:

The factor base is rather large since we have primes besides all (H+c) terms.

Lots of equations are needed to solve the system.

After finding g, we still need to find the logarithm of the original primitive root in terms of our collected weights.

However, as mentioned by the authors, these deficiencies are not serious and finding (H+c) terms that factor through our list of primes is optimal. This prevents additional new equations.

2.2 Gaussian Integer Sieve

Gaussian integers are complex numbers with integer coefficients and they are closed under both addition and multiplication (Cryptohack, 2021)2.

We recommend (William, 2020)3 and (Conrad, 2020)4 for friendly introductions to Gaussian integers.

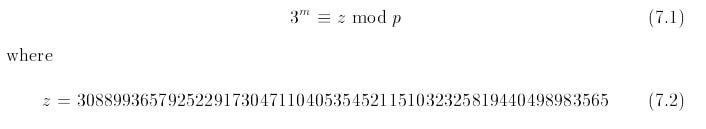

The (LaMacchia & Odlyzko, 1991) paper focuses on the problem below:

where p is a 192-bit prime number:

p = 52136194242715203716870141131701823417775636036803544167792.2.1 Important Definitions

Here are some important definitions from algebraic number theory (Tao, 2020)5 that will help us through the coding guide:

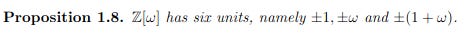

Unit - a number

uis called a unit ifudivides 1, that is, there exists a numbervsuch thatuv = 1.Irreducible number - a number

pis irreducible if it is not zero or a unit, andpcannot be written as the product of smaller thing. (It’s a generalized version of a prime number)Unique Factorization Domain (UFD) - a number system where every number, except 0 and a unit, can be written as a product of irreducible prime numbers.

Class number of 1 - a ring of integers that permits a unique factorization domain. (Weisstein, 2025)6

Heegner numbers - imaginary quadratic fields with unique factorization (have class number 1). (OEIS, A003173)7

There are only 9 Heegner numbers: -1, -2, -3, -7, -11, -19, -43, -67, -163.

Note that Heegner numbers are all negative.

Quadratic residue - we say that an integer

mis a quadratic residue (QR) modulonif there exists an integerxfor which x2 ≡ m mod (n).If it has a square root mod n then it’s QR.

A number is QR if its legendre symbol mod p is 1.

2.2.2 Finding a Number Field

*Italicized words are from the definitions in Section 2.2.1

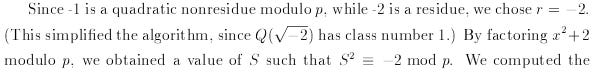

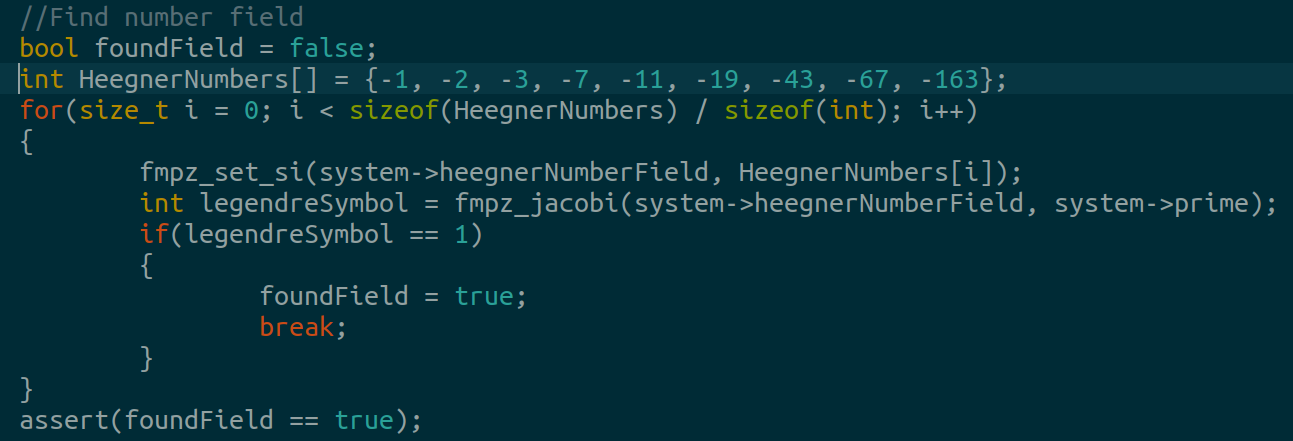

We search the set of Heegner numbers to find the smallest quadratic residue of class number 1 modulo our prime using the fmpz_jacobi function.

*Jacobi symbol is a generalized version of the legendre symbol.

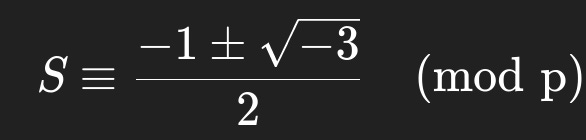

We also need to find S, the square root of the heegner number field.

*Finding S by square root only applies to Gaussian integers. Section 3.0 demonstrates finding S for Eisenstein integers.

In Python, this resembles:

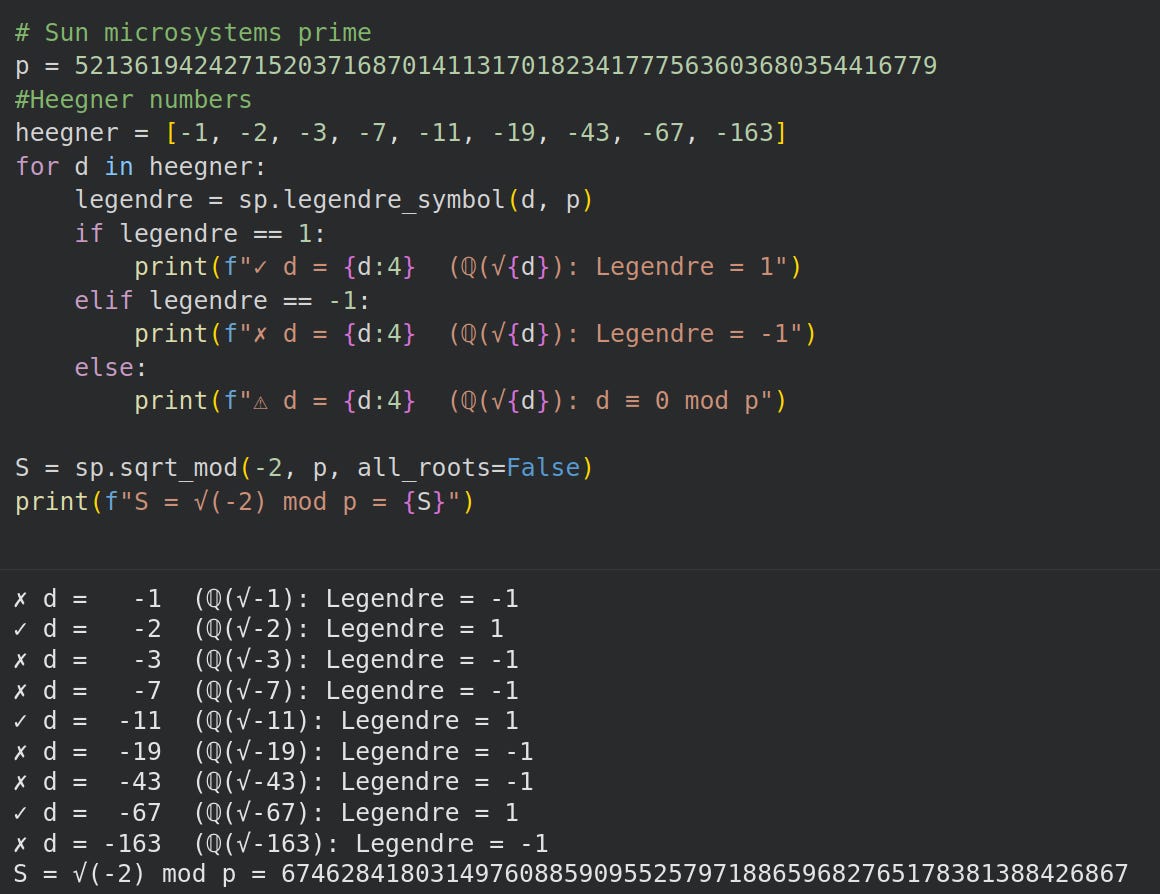

We find these number field parameters:

Heegner Number (r): -2

Heegner Root (S): 6746284180314976088590955257971886596827651783813884268672.2.3 Finding V and T

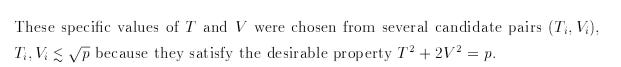

Next we find T and V such that T2 ≡ rV2 mod p such that:

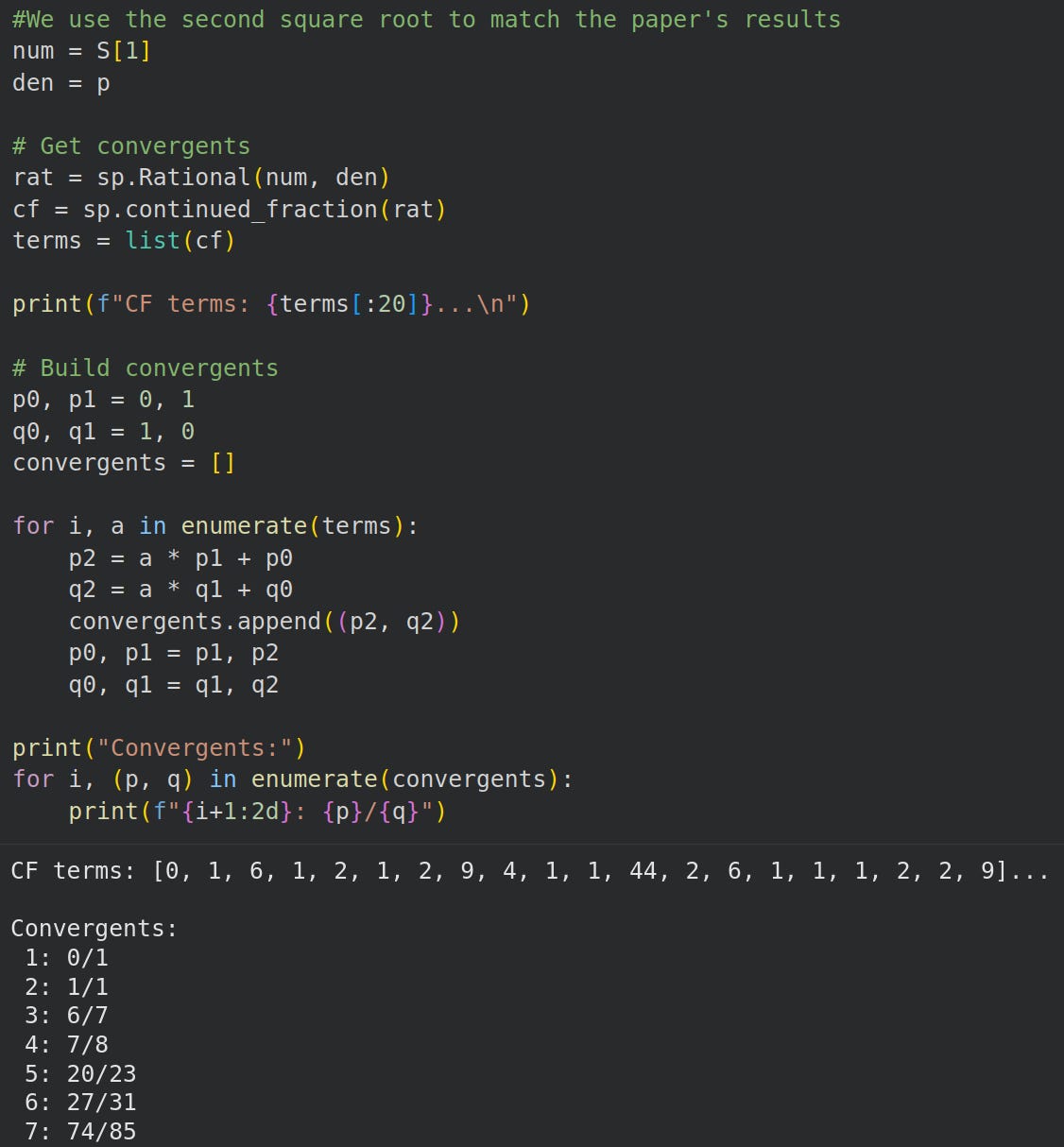

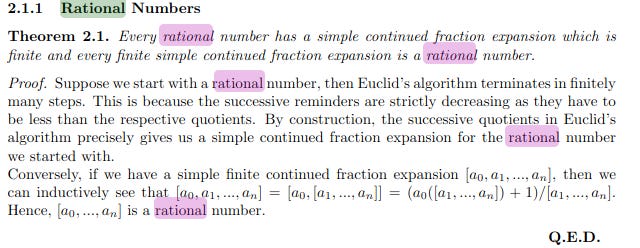

We search for T and V in the continued fraction convergents of (S / p) using Euclid’s algorithm (Gautam, 2016)8:

*Remember, this paper’s from 1986 so the approach is outdated lol

In Python the code, including the starting coefficients of the continued fraction:

You can verify the exapnsion with this online continued fraction calculator and the input:

4538991006240022762827918587372993682094798425298965989912/5213619424271520371687014113170182341777563603680354416779*if you get an unexpected character error then remove the spaces around the division symbol‘/’

Now we search through the numerator and denominator pairs for T and V and observe two things:

The first time fails. We need to use the other root (p - S).

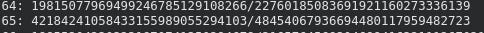

Our desired values occur in the denominator:

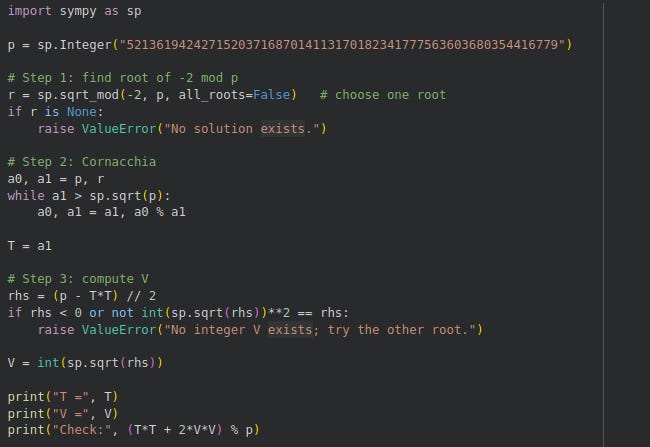

There’s a shortcut to solving this called Cornacchia’s algorithm (Praxix, 2012)9:

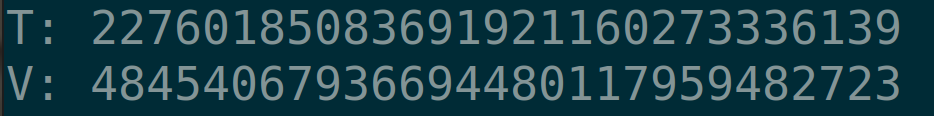

We obtain T and V:

T: 22760185083691921160273336139

V: 484540679366944801179594827232.2.4 Finding Smooth Numbers

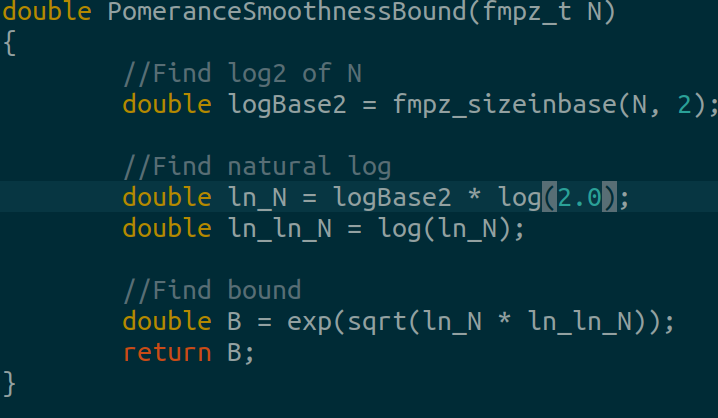

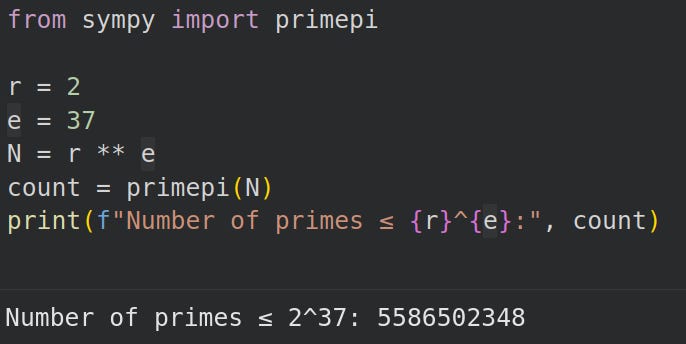

First, we set a smoothness bound as we did before in the Pell Index Calculus paper:

In our case, our small factor base is prime numbers upto 237 and the large prime factor base from (Lenstra & Manasse, 1994)10 upto 55 bits:

Bound0: 37 bits

Bound1: 55 bitsAlternatively, you can use prime counting function to determine the size of the factor base:

Then we use the medium prime trick (LaMacchia & Odlyzko, 1991) to find smooth relations close to the square root of p.

Find x and y using an algorithm called rational reconstruction. In FLINT we call

fmpq_reconstruct_fmpz().

So we collect relations of the form:

XF_YF → Full relation factors completely over factor base.

XF_YP → 1 large prime (in Y) outside factor base.

XP_YF → 1 large prime (in X)

XP_YP → 2 large primes (one in X, one in Y)

2.2.5 Gaussian Integer Factorization Trick

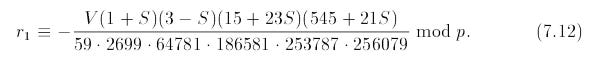

Finally, we use the factorization trick in Equation 7.12 to make our medium-sized primes even smaller:

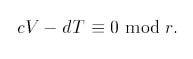

The authors use contined fractions to find small integer solutions (Elkies, 2011)11 to the equation:

*r here is the medium prime, not the heegner number field

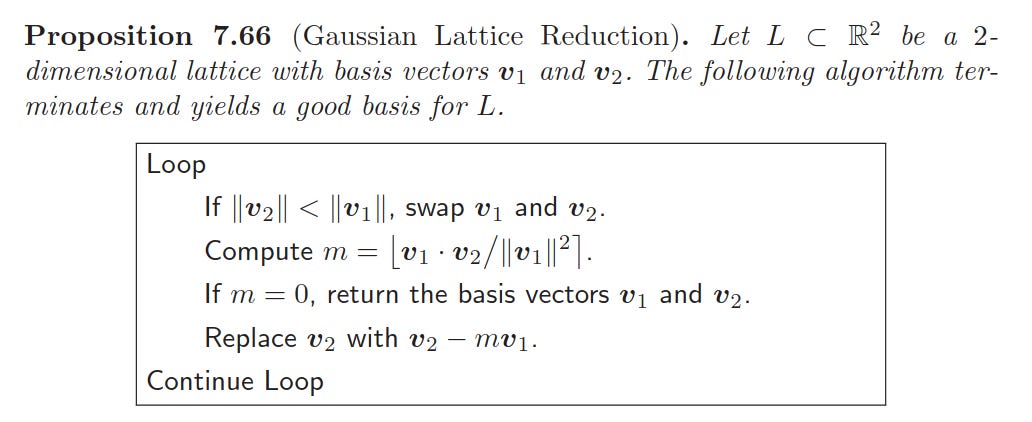

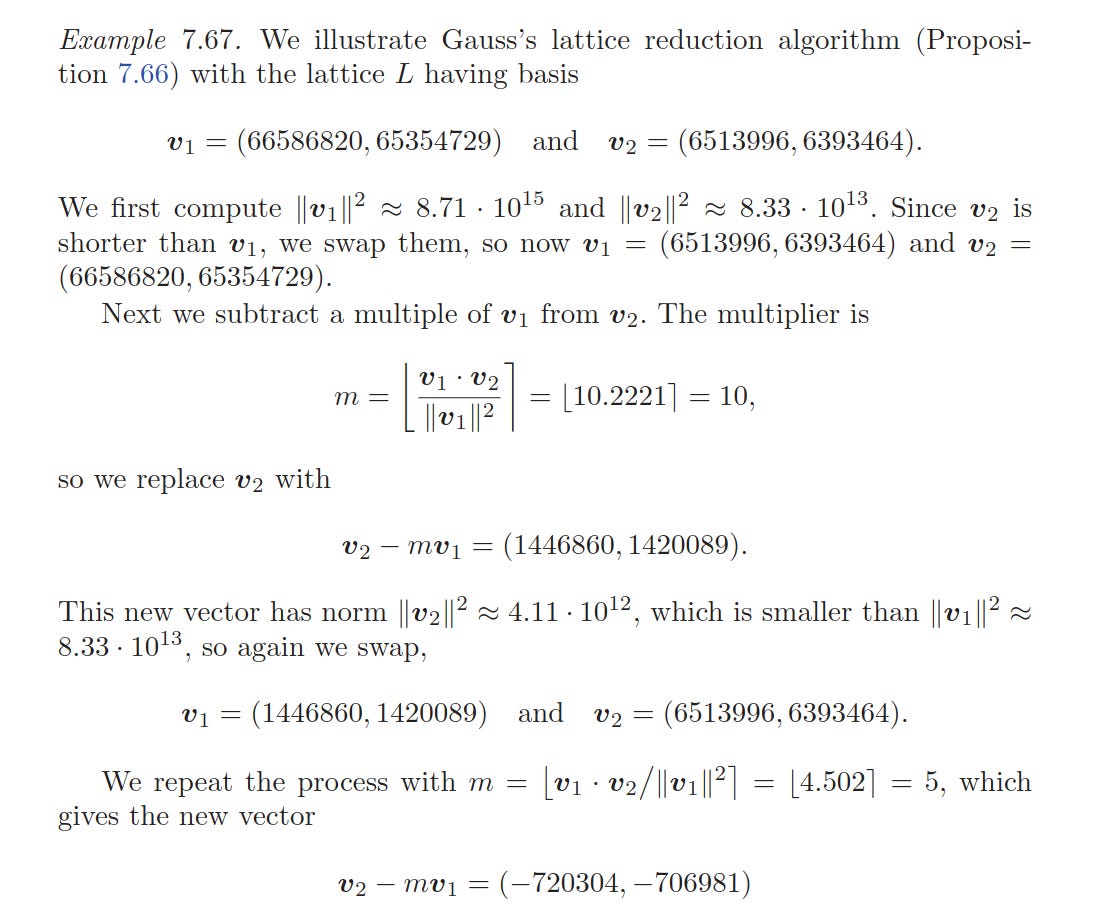

This paper is from 1991 so they overexplained Gaussian Lattice Reduction in Dimension 2 (Hoffstein et al., 2015)12.

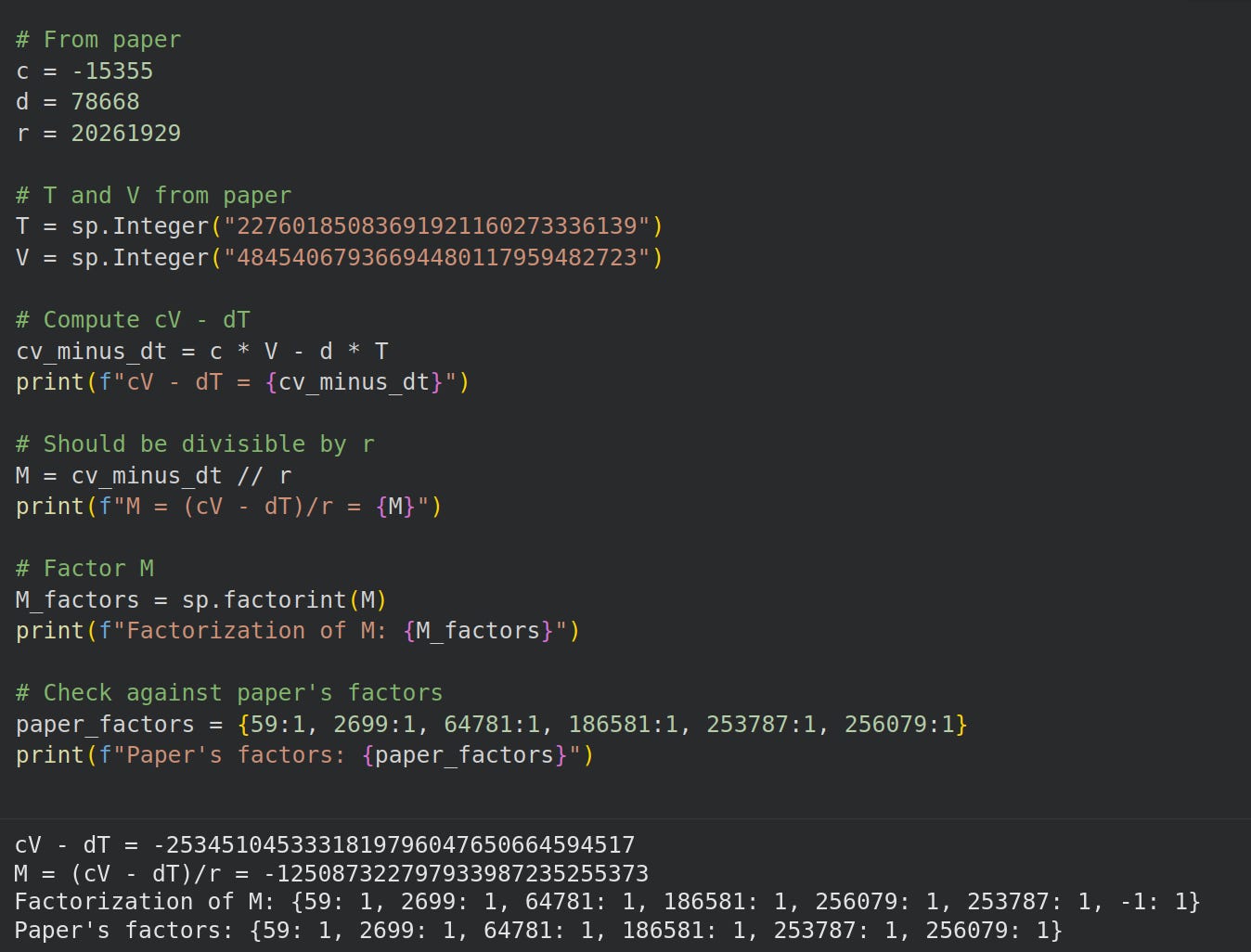

Let’s walk through the paper’s example for 20261929 where T and V are shown above:

We need two basis vectors for reduction and easily find:

Kernel basis (set c to T and d to V)

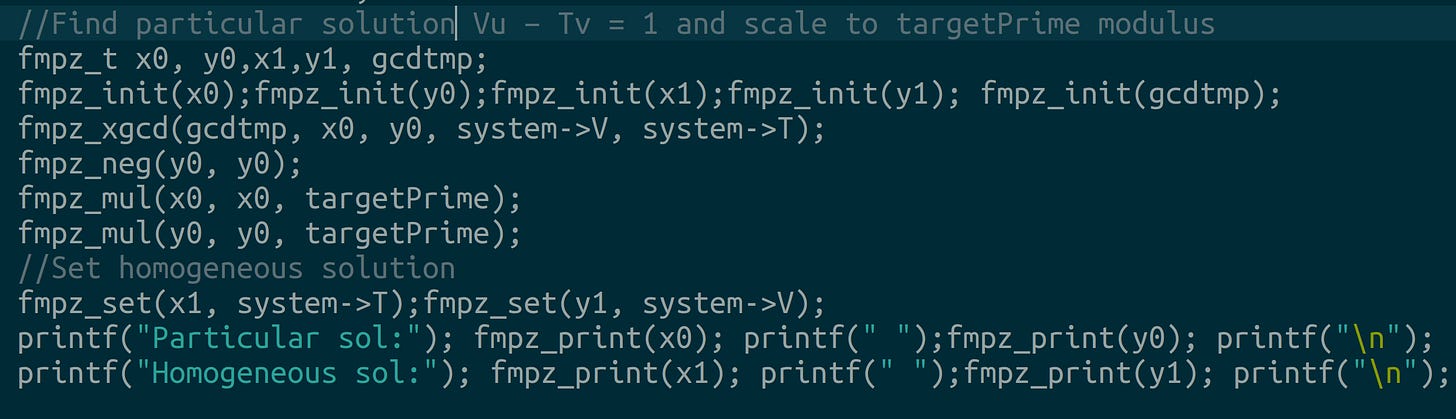

Extended gcd basis (use the extended gcd to find a particular solution):

Particular sol:-59673551245166860509291709922547017, -127038787049622592945843517621047980 Homogeneous sol:22760185083691921160273336139, 48454067936694480117959482723

Next we write a brief Gaussian lattice reduction function:

Here’s a gist example in FLINT. We get the shortest solution:

(3683, 2244)If you’re confused then you can follow by hand:

Now check if

(cV-dT)/rfactors into small primes.If it doesn’t then we test other linear combinations

v = (x0,y0) + k*(T,V)If it does then we have a nice denominator. Our search yields a vector and

191717(an 18 bit number) in its factorization:*Remember

20261929is a 24 bit number. We saved 6 bits!Vector(c,d): (692011, 3827045) Factors: 2 ^ 1, 17 ^ 1, 53 ^ 1, 157 ^ 1, 3067 ^ 1, 18553 ^ 1, 22189 ^ 1, 191717 ^ 1, 38609 ^ 1,

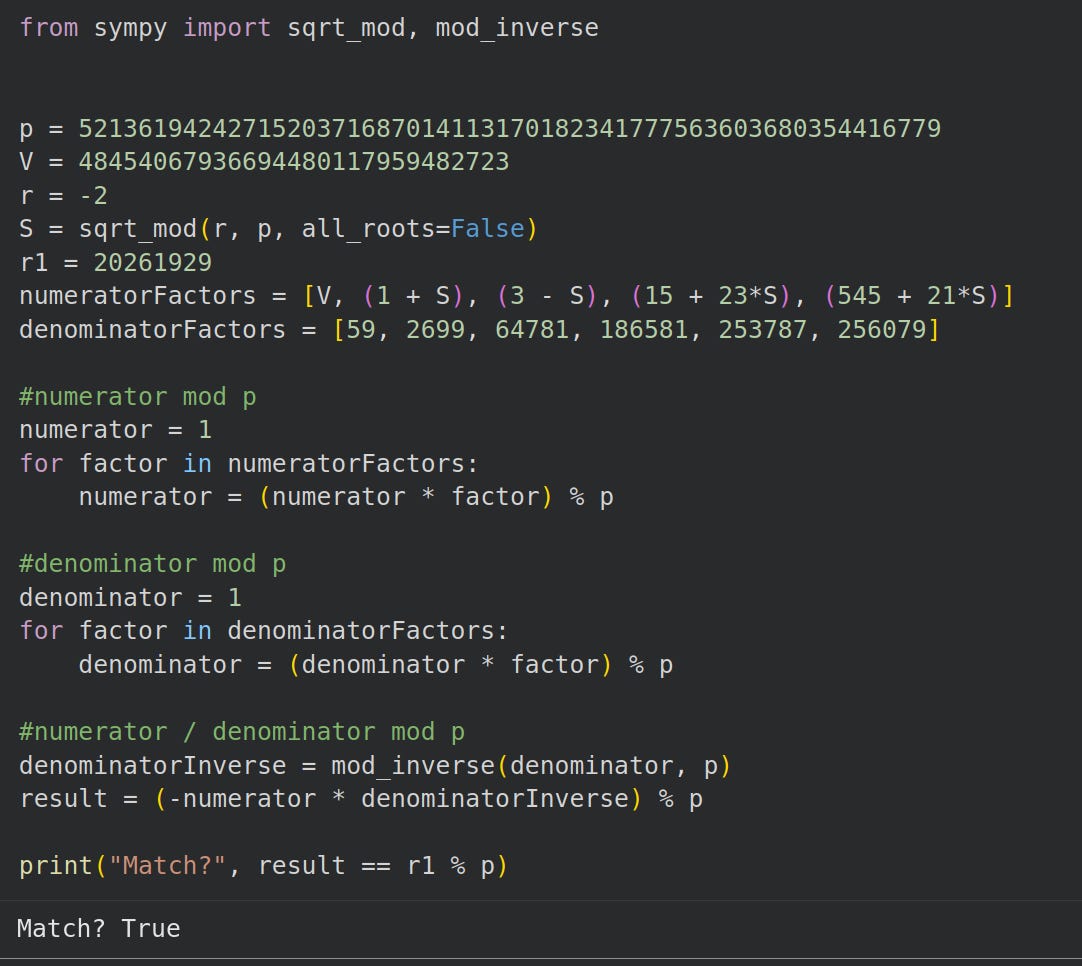

Now we factor the numerator over complex numbers using the relationship from page 9 and steps from (Alpertron, 2025)13:

cV-dT = V(c+ds) mod p`.Step 1: Find the prime factorization of the norm of c+ds

(c,d): (692011, 3827045) heegnerNumberField (s): -2 Norm: 29771426088171 Norm factors: 3 ^ 3, 163 ^ 1, 89083 ^ 1, 75937 ^ 1Step 2: Find the legendre symbol for each prime in the norm factorization where

legendre 0: p ramifies - p appear as squareRoot p with exponent divided by 2 legendre -1: p inert, so p is a prime in complex field - p appears in prime factorization unchanged legendre 1: p splits as (a+b√d)(a-b√d), find a,b like in Section 2.2.3Then factorize.

In Python, this method of finding smaller primes resembles:

For the sake of completion, our factor base is entirely integers. Observe that equation 7.12 holds over the integers:

We are done with the paper!

3.0 Bitcoin Modifications

I recommend skimming the definitions in Section 2.2.1 if you jumped here

Bitcoin’s field characteristic prime number is given in the offical SEC whitepaper (Certicom, 2010)14:

p = 115792089237316195423570985008687907853269984665640564039457584007908834671663The largest factor of p-1 is a 236 bit prime and this is important for index calculus:

(p-1) factors = 2 * 3 * 7 * 13441 * 205115282021455665897114700593932402728804164701536103180137503955397371However, the smallest Heegner number (definition in Section 2.2.1) for the bitcoin prime is -3.

3.1 Ring of Eisenstein Integers

*We defined all these foreign words earlier in Section 2.

The UFD with Heegner number (-3) is defined over the ring of Eisenstein integers (Weisstein, 2025)15.

We follow (Lemvig, 2024)16 to modify the algorithms introduced in Section 2.0

Change 1: Integer Form

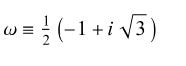

The Eisenstein integers are complex numbers of the form

a+bwwhereaandbare normal integers andwis a cube root of unity (Weisstein, 2025):

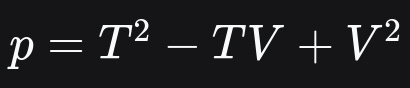

Change 2: Norm Calculation

The norm changes to:

Units are elements of norm 1 and the Eisenstein ring has 6 units:

Change 3: S, T and V Parameters

pmust be a number where legendre (-3/p) = 1.This means -3 must be a quadratic residue modulo p.

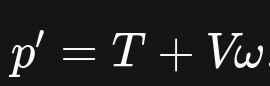

p`takes the form:We find

TandVsuch that :We use the modified version of Cornacchia’s algorithm from Section 2.2.3 (Woba, 2024)17

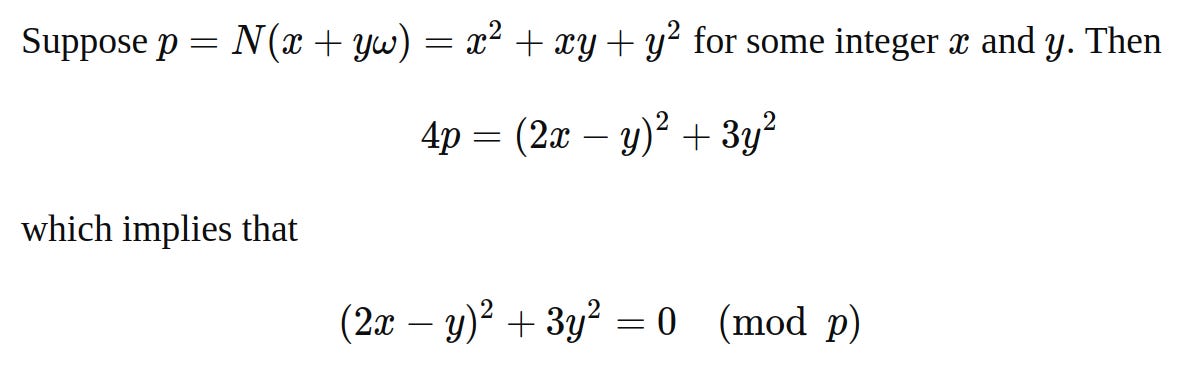

Let

U = 2T - Vand sub into T2−TV+V2Solving via Cornacchia’s algorithm U2+3V2 = 4p gives us

Tand V.

Sis a non-trivial cubic root of unity modulopfound by solving:If your root of unity fails to solve for T and V, then use the other one. Here’s a C script that finds

T,VandSfor different primes.

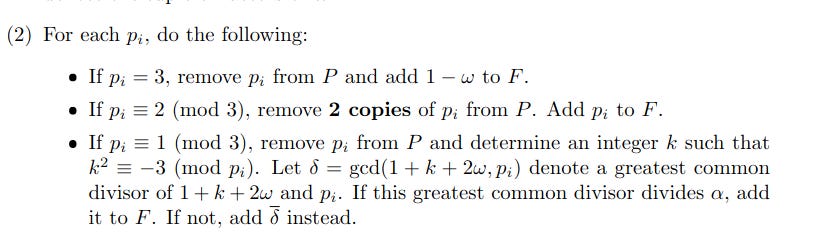

Change 4: Prime Factorization Algorithm

As we saw in Section 2.2.5, we first compute the norm and its prime factorization.

For each prime:

Change 5: Finding a primitive root modulo T+Vw

We find a prime primitive root modulo p, test if it splits -3, then find a T,V representation. Here’s a sample C script.

3.2 Worked Example

We work with the prime number 20959 with Heegner number 3 and these parameters:

Integer Prime: 20959

Integer Prime-1: 20958

Integer Primitive Root: 97

Norm factors:

(2 ^ 1)(3 ^ 1)(7 ^ 1)(499 ^ 1)

Heegner Number: -3

RootOfUnity (S): 1631

T: 167

V: 77

Complex prime: (167 + 77√-3) Norm = 20959

Complex PrimitiveRoot: (11 + 3√-3) Norm = 97

For bitcoin:

Integer Prime: 115792089237316195423570985008687907853269984665640564039457584007908834671663

Integer Prime-1: 115792089237316195423570985008687907853269984665640564039457584007908834671662

Integer Primitive Root: 691

Norm factors:

(2 ^ 1)(3 ^ 1)(7 ^ 1)(13441 ^ 1)(205115282021455665897114700593932402728804164701536103180137503955397371 ^ 1)

Heegner Number: -3

RootOfUnity (S): 55594575648329892869085402983802832744385952214688224221778511981742606582254

T: 367917413016453100223835821029139468249

V: 303414439467246543595250775667605759171

Complex prime: (367917413016453100223835821029139468249 + 303414439467246543595250775667605759171√-3)

Norm = 115792089237316195423570985008687907853269984665640564039457584007908834671663

Complex PrimitiveRoot: (19 + 30√-3) Norm = 691We are ready to go!

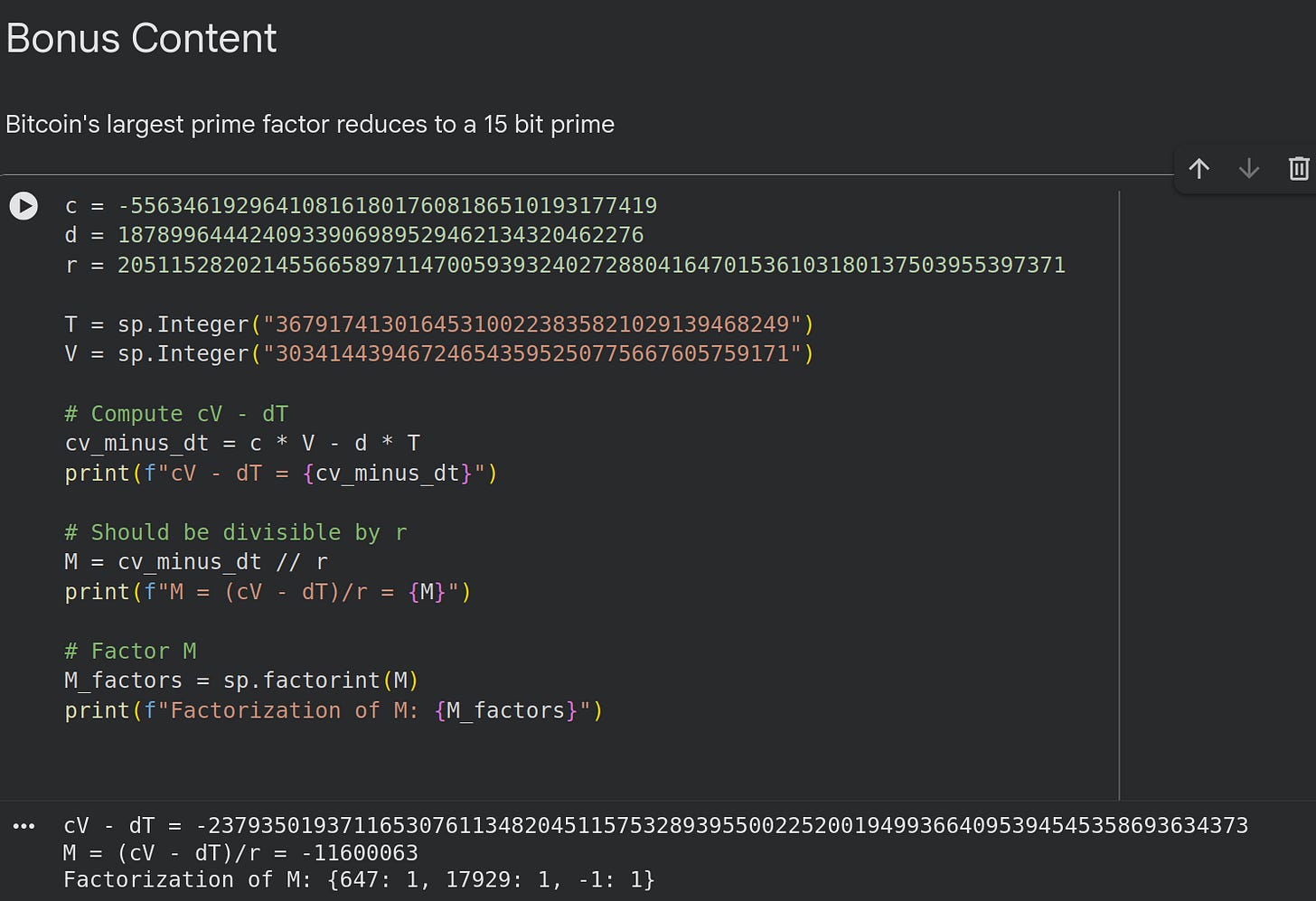

Bonus content

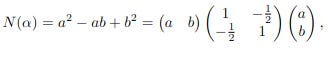

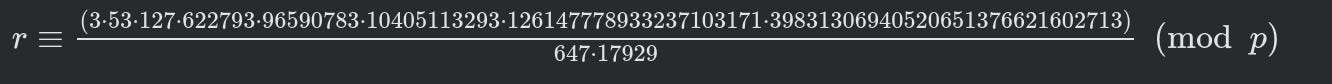

I encountered the most bizarre thing. In Section 3.0, we saw the bitcoin field characteristic prime has a 236 bit prime factor:

205115282021455665897114700593932402728804164701536103180137503955397371Using these T, V and S values:

RootOfUnity (S): 55594575648329892869085402983802832744385952214688224221778511981742606582254

T: 367917413016453100223835821029139468249

V: 303414439467246543595250775667605759171we find the c, d (from Section 2.2.5) values:

C: -5563461929641081618017608186510193177419

D: 1878996444240933906989529462134320462276This is where it gets sooo strange: cV-dT/r factors into a thing with 15 bits:

cV - dT = -2379350193711653076113482045115753289395500225200194993664095394545358693634373

M = (cV - dT)/r = -11600063

Factorization of M: {647: 1, 17929: 1, -1: 1}The numerator has a 95 bit prime:

39831306940520651376621602713We went from 236 bits to 95 and 15 bits. IMO this should be statistically impossible.

So we can rewrite the largest prime factor (r) as:

r = (cV - dT)/ M

r = (3 * 53 * 127 * 622793 * 96590783 * 10405113293 * 126147778933237103171 * 39831306940520651376621602713) /(11600063) mod por

This is the final cell in our colab notebook.

*Trump defunded my math PhD and now I identify as an internet math autist. Could one or two of you subscribe and help me pay December’s rent while I figure things out.

4.0 Further reading

Here are other chapters from our attempt at accessing Satoshi’s wallet.

Available Chapters

Chapter 1 : A Programmer’s Introduction to Elliptic Curves.

Chapter 2 : What Every Programmer Needs To Know About Conic Sections (To Attack Bitcoin)

Chapter 3 : The Discrete Logarithm Problem and the Index Calculus Solution.

Chapter 4: Smart Attack on Elliptic Curves.

Chapter 5: The US Government Hid a Mathematical Backdoor in another Elliptic Curve.

Chapter 6: Hacking Dormant Bitcoin Wallets in C coding guide.

Chapter 7: Pollard’s Rho and Kangaroo Collision Searching.

Chapter 7: If you’re smart why are you poor? Elliptic Curve Edition.

References

LaMacchia, B. A., & Odlyzko, A. M. (1991). Computation of discrete logarithms in prime fields. Designs, Codes, and Cryptography, *1*(1), 46–62. PDF.

Lenstra, A & Manasse, M. (1994). Factoring with Two Large Primes. Mathematics of Computation, Vol. 63, No. 208 (Oct., 1994), pp. 785-798. American Mathematical Society.

Elkies, N,. (2011). [Answer] Which Diophantine equations can be solved using continued fractions?. Link.

Woba, M.D. (2024). Representation of an Integer by a Quadratic Form through the Cornacchia Algorithm. Applied Mathematics, 15, 614-629. https://doi.org/10.4236/am.2024.159037