This is part of our Practical Lattice Attacks on Quantum-Safe Cryptography series. As usual, here’s the Google Colab notebook and here’s the GitHub.

Part 1: We coded the 1996 paper on the Hidden Number Problem as well as the 2020 paper that improves on the LLL solution.

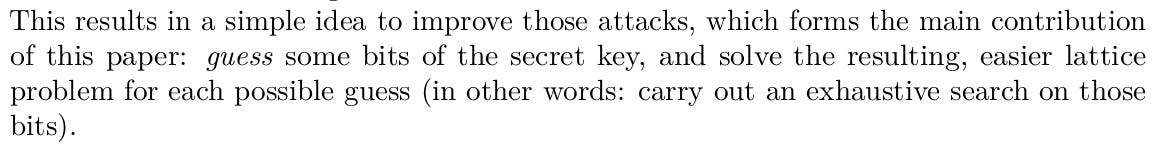

Part 2(we are here): This paper demonstrates how to improve attack success by ‘guessing some bits of the secret key’.

1.0 Paper Introduction

Part 1 introduced the hidden number problem: the challenge of recovering a secret hidden number given partial knowledge of its linear relations (Surin & Cohney, 2023)1

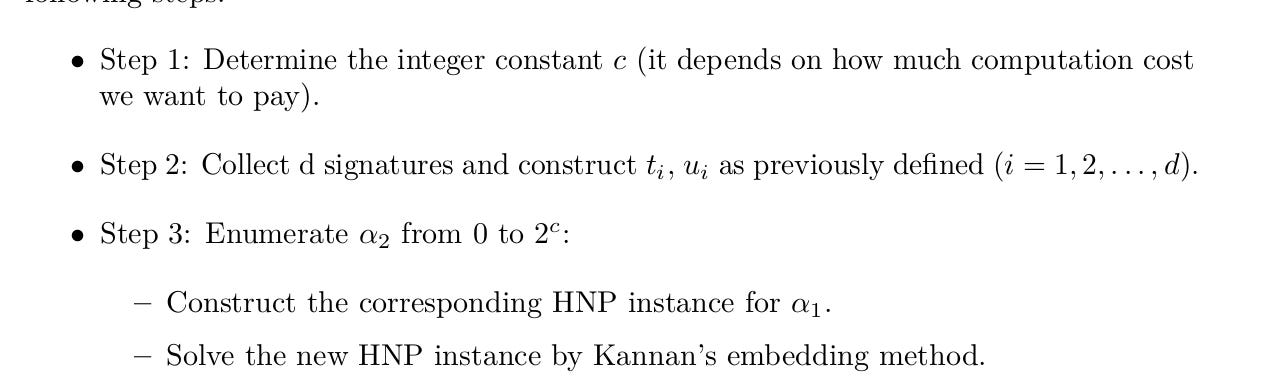

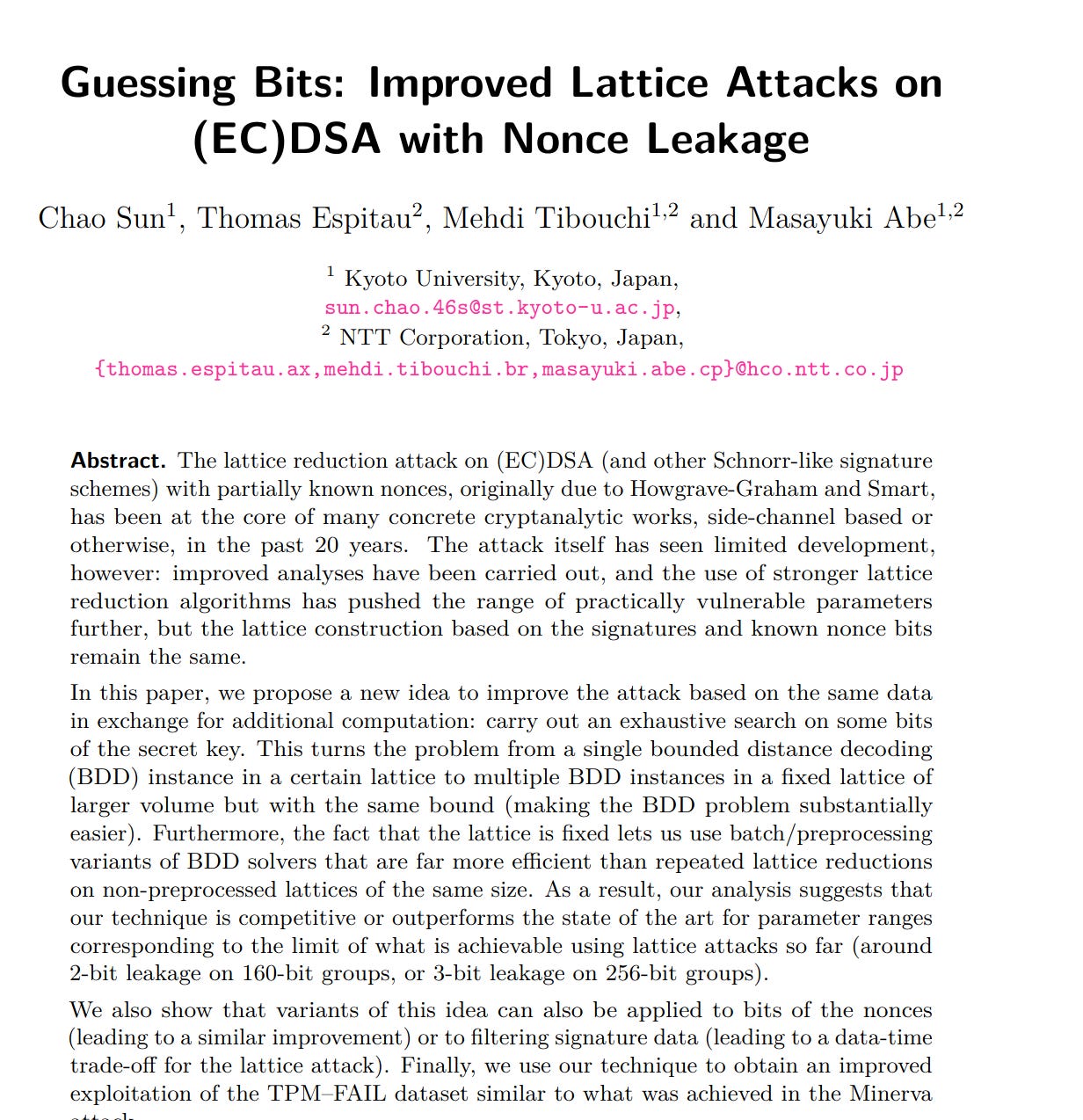

The paper, Guessing Bits: Improved Lattice Attacks on(EC)DSA with Nonce Leakage (Sun et al., 2021)2, improves on the (Albrecht & Heninger, 2020)3 lattice-based HNP by:

Guessing some secret key bits to increase attack success probability.

Decomposing the secret key into batches to recover parts of the secret. ie. it’s no longer an ‘all-or-nothing’ approach.

1.1 Variable Definitions

Here are the variables defined in (Sun et al, 2021):

α - rhe secret key

q - the modulus of our secret key.

t - a single known observation in a hidden number problem instance.

l - the number of leaked bits.

d - the number of observations.

n - lattice dimension.

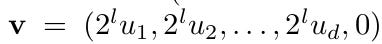

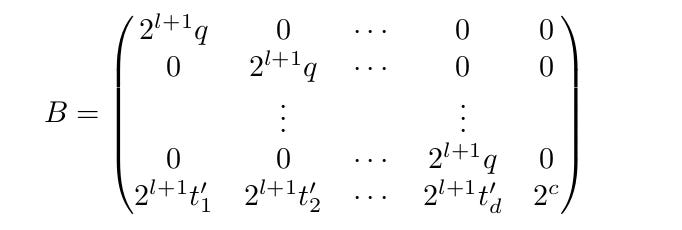

B - a lattice basis matrix.

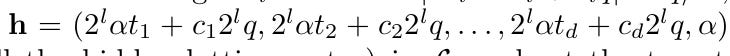

h - the hidden vector.

v - the target vector.

e - the difference (h-v)

2.0 Lattice Construction Starter

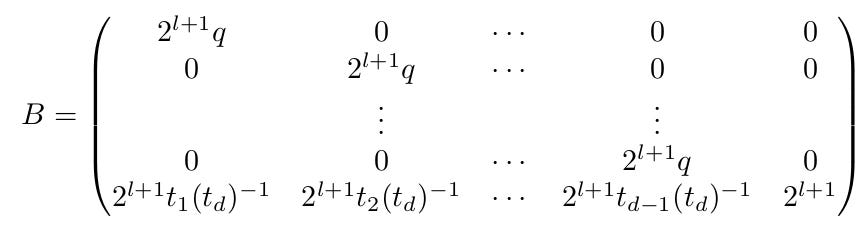

The authors start from the lattice constructed in Part 1 and incorporate the techniques we saw before: recentering the lattice and removing the first row to make our target the shortest vector.

2.1 Recentering Technique

(Sun et al., 2021) recenter by multiplying by 2. Remember, in part 1 (Albrecht & Heninger, 2020) achieved the same by subtracting half the error bound.

2.2 Projected Lattice Technique

The authors further borrow the ‘remove the first row’ technique from part 1’s (Albrecht & Heninger, 2020) lattice and call this the projected lattice technique.

Observe that we recover the secret key using the equation

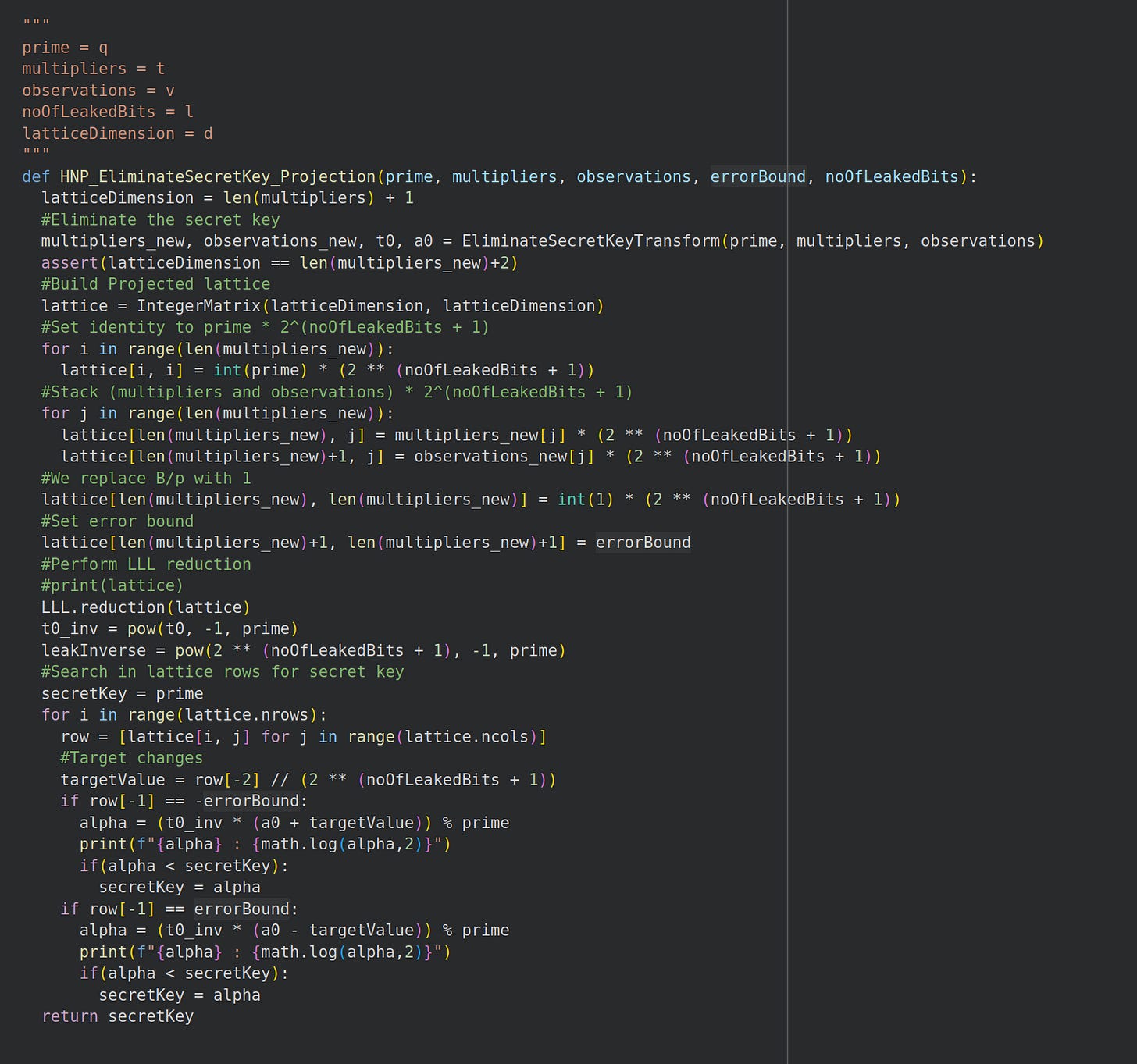

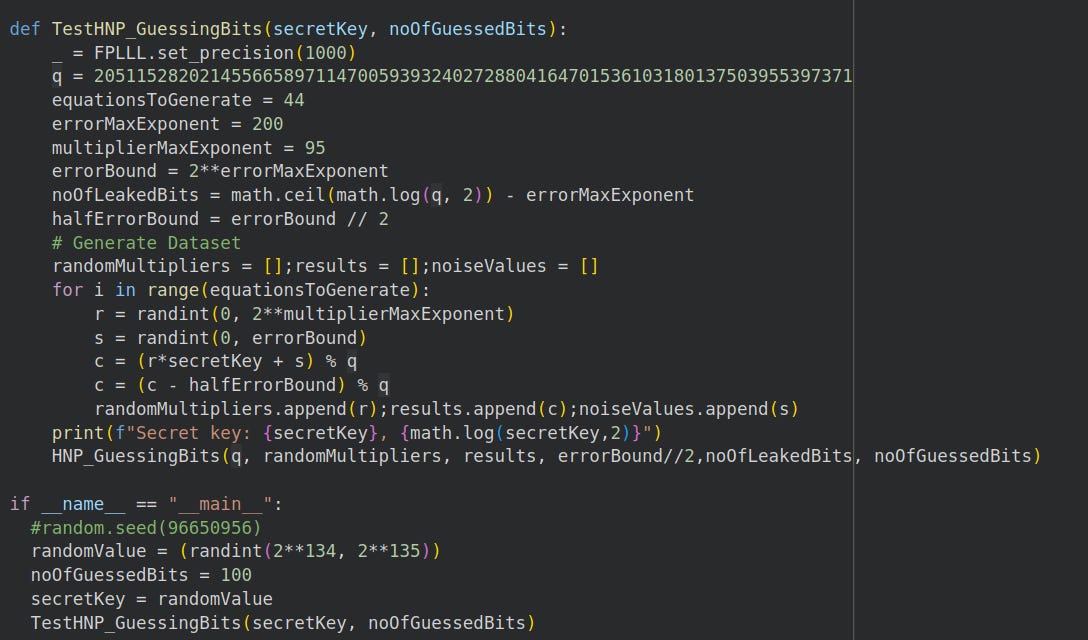

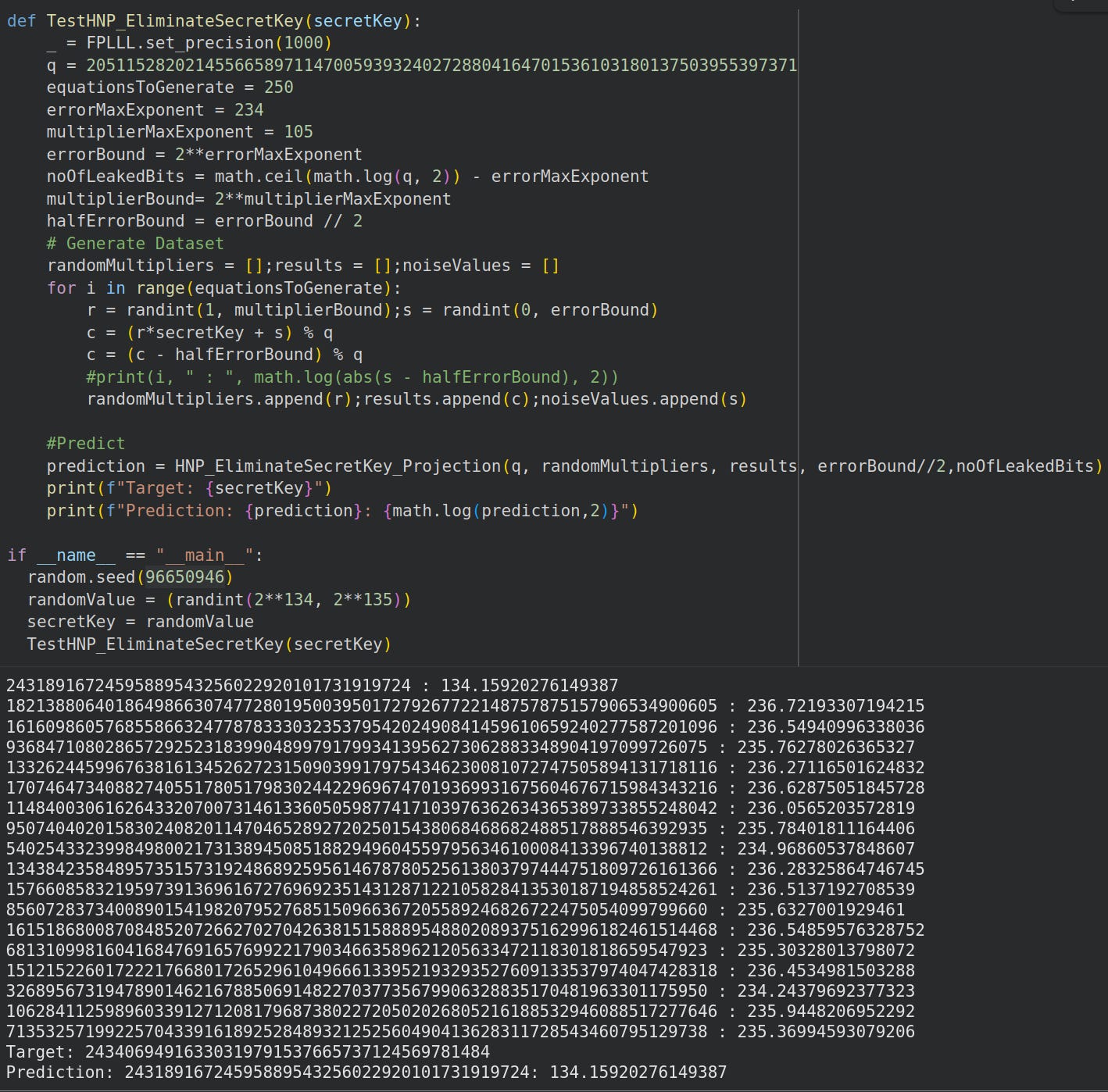

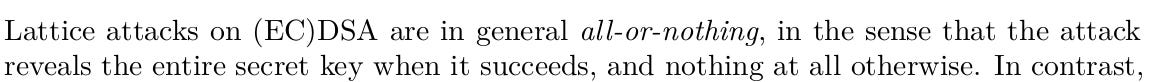

2.3 Python Code

We code the lattice upto this point on Google Colab:

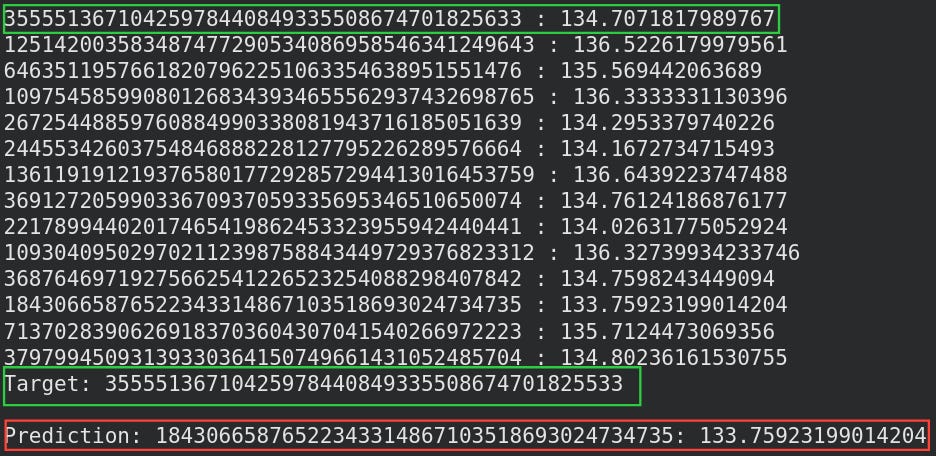

Then we test to observe that we recover the exact secret key:

3.0 Increase Lattice Volume

Here’s the paper’s thesis: we don’t need to find the entire secret key at once, we can split it and search in batches.

More formally, we can modify the lattice to increase its volume while the error vector remains constant.

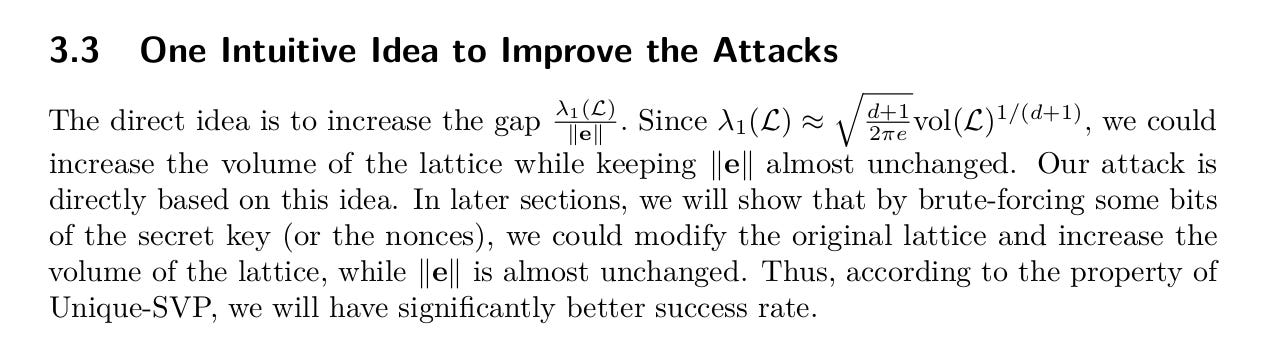

3.1 How to Increase Lattice Volume

There are two ways to increase lattice volume:

Multiply the unknown secret key by a constant.

This is possible on elliptic curves lol.

Multiply the known observations by a constant.

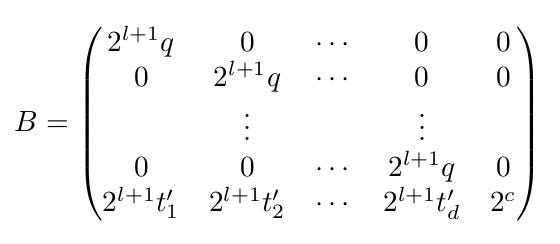

3.2 Increasing Volume via Multiplying Observations by a constant

(Sun et al., 2021) increase lattice volume by multiplying observations by a constant. They construct a lattice of the form:

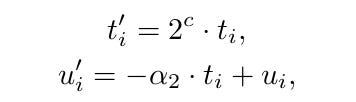

where c is a constant and

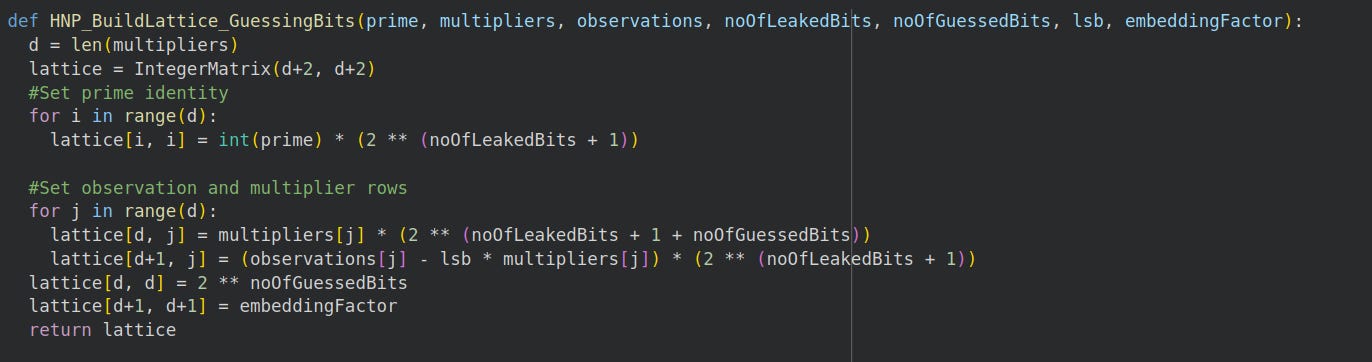

In Python, we construct the lattice like this:

To find the target vector, we take the second last integer in a reduced lattice row, set the last c bits to 0, then enumerate different possibilities.

In pseudocode:

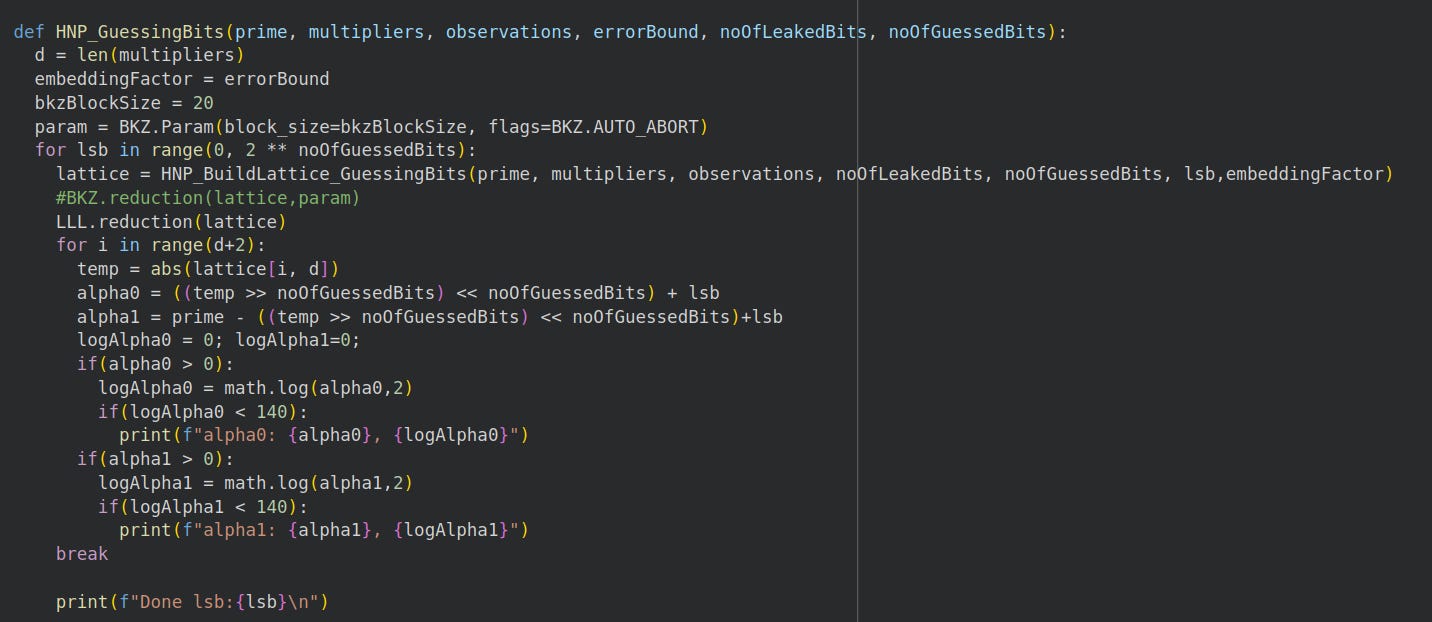

In Python, we have:

This lattice construction works best when we know the bitlength of our secret key.

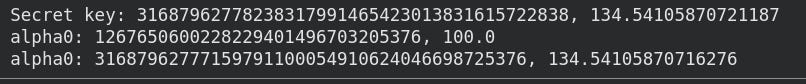

So we test it on a 237 bit prime, secret key is 135 bits, we guess 100 least significant bits:

Our code succeeds in recovering the first 35 bits. The last 100 bits are wrong (as expected)

3.3 Increasing Volume by Multiplying Secret Key by a Constant

We increase the volume of the lattice by multiplying the secret key by a constant, 2^c.

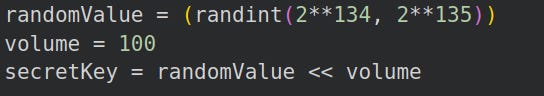

In our python code, we make the following changes:

Multiply the secret key by a large multiple of 2:

Multiply our embedding factor by the same multiple of 2:

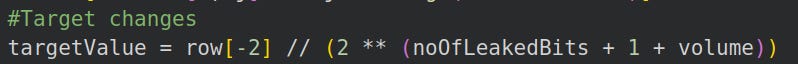

Incorporate the volume into the target calculation

Ultimately, our prediction logic will FAIL. However, observe that our desired target appears in the generated list of possible alphas (it’s just not the smallest anymore)

Observations:

Prediction (red) is wrong.

Target (green at the bottom) ends with 5533.

Possible target generated by LLL (green at the top) is neither the shortest vector and ends with 5563.

The authors demonstrate we can search for an approximate target and brute force the wrong bits afterwards.

We reproduced the paper on Colab. The authors also provide a Sage implementation on GitHub but I found it incoherent lol.

4.0 Bonus Content

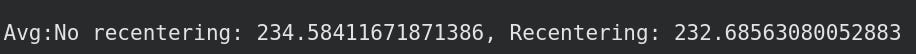

Here’s a bizarre observation. One can perform both the author’s recentering trick (increasing the number of leaked bits by 1) as well as (Albrecht & Heninger, 2020) ‘recentering by subtraction’ trick.

It doesn’t always work but when it does, we gain an extra bit in savings. This is the final cell in the Google Colab notebook.

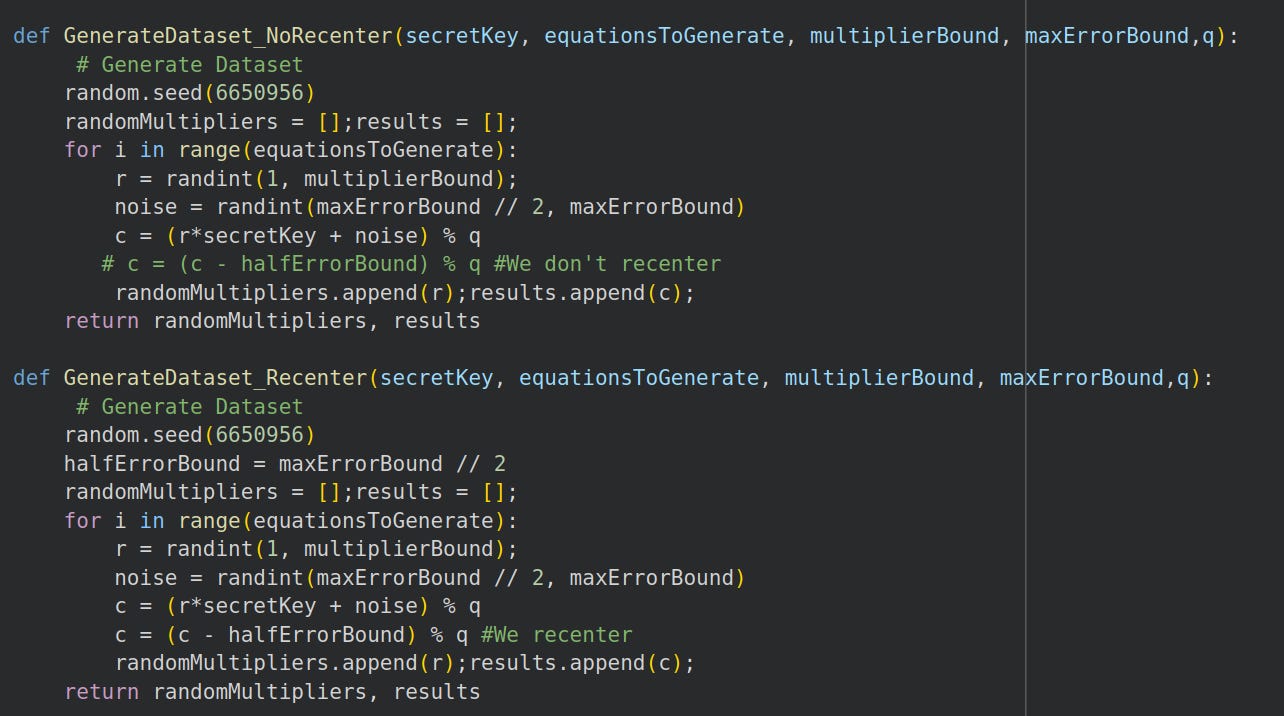

4.1 Importance of Recentering

Bounding your errors is the most important part of lattice construction and recentering works absolute wonders.

When your error lies in a known certain range then spend all your time recentering.

Say our noise lies pretty close to the maximum, something like :

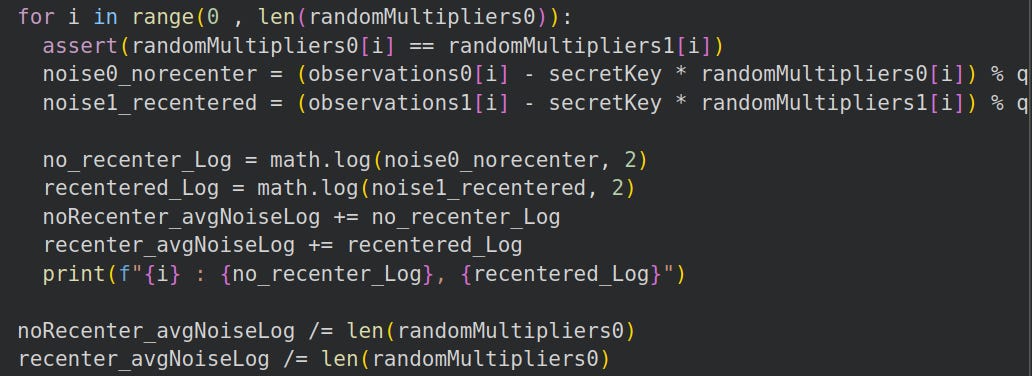

noise = randint(maxErrorBound // 2, maxErrorBound)We generate identical datasets but one recenters and the other doesn’t.

The noise term is found as:

noise = (observation - secretKey * multiplier) % qSo we can compare the noise term for the identical datasets in a for loop:

Observe that the average noise upon recentering is much lower than without

However, if you don’t know your bounds then you’ll probably shoot yourself in the foot.

You made it this far. Here are some free gpu credits.

If you haven’t already, here’s 12 months of Perplexity Pro for free.

References

Surin, J., & Cohney, S. (2023). A Gentle Tutorial for Lattice-Based Cryptanalysis. University of Melbourne. Cryptology ePrint Archive. PDF Link.

Sun, C., Espitau, T., Tibouchi, M., & Abe, M. (2021). Guessing Bits: Improved Lattice Attacks on (EC)DSA with Nonce Leakage. IACR Transactions on Cryptographic Hardware and Embedded Systems, 2022(1), 391-413. https://doi.org/10.46586/tches.v2022.i1.391-413

Albrecht, M.R., & Heninger, N. (2020). On Bounded Distance Decoding with Predicate: Breaking the “Lattice Barrier” for the Hidden Number Problem. IACR Cryptology ePrint Archive.